When Amanda Gorman performed her poetry at US President Joe Biden’s inauguration, she ignited a media frenzy. Part of the reason was her powerful and poignant work, but there was also another factor: her age. At 22, Gorman is America’s youngest-ever inaugural poet, after becoming the first national youth poet laureate at 19. Her much-praised performance led to viral memes, multiple book deals and a contract with talent management agency IMG Models.

Gorman joins the ranks of other young super-achievers venerated by society, like Norwegian chess player Magnus Carlsen, who became a grandmaster aged 13; Argentine football player Lionel Messi, who joined Barcelona’s pro team at 17; classical-music prodigy Alma Deutscher, who at 10 was the youngest British composer signed by an agent; and Pakistani women’s education activist Malala Yousafzai, who at 17 was the youngest Nobel Peace Prize recipient. History books will record not only their talents, but the fact that their achievements came so young.

Yet it’s not just the most famous prodigies that Western culture idolises. We glorify young achievement across the board through media awards like Forbes and Inc.’s 30 Under 30 lists, Glamour’s College Women of the Year awards and Time’s recently-inaugurated Kid of the Year awards. Such lists spotlight young people accomplishing impressive feats in art, science and business, many of which have a wider positive impact.

It’s clear that we’re fascinated by success that comes at an early age. In fact, we view young people’s achievements differently to those of older people because of our perceptions around innate talent as well as age-related stereotypes and media sensationalism. Yet while young achievements can certainly spark awe, they can also induce envy or negative comparison. Understanding how we respond to young brilliance could help us put aside our biases – and better appreciate the inspiration these young people offer.

‘Genius is effortless’

There are several reasons why we’re primed to extol the accomplishments of the young, including attitudes toward giftedness, societal norms about life milestones and evolving cultural expectations of young people.

A key factor is the misconception that talent is innate, rather than the result of years of labour. “There’s an idea that genius is effortless, and that hard work is somehow less fascinating or valuable,” says psychologist Tanja Gabriele Baudson, who researches giftedness, stereotypes and identity development at Mensa Germany and the Institute for Globally Distributed Open Research and Education. Research shows that effortless achievement is often equated with “authentic” intelligence in Western societies, while hard work can be seen as “boring” and a sign of a lack of intelligence, according to a 2014 study of British and Swedish students.

There’s an idea that genius is effortless, and that hard work is somehow less fascinating or valuable –Tanja Gabriele Baudson

When young achievers emerge, we assume they must be unique talents because they haven’t had time to put in those years of effort. Yet they too have worked for their success; Gorman, for instance, had to overcome an auditory-processing disorder and speech impediment in childhood; Carlsen began playing chess at age five; and Messi started playing soccer at four. Their accomplishments aren’t just the result of natural talent, but years of practice. “Outstanding achievement in any domain requires both innate ability and hard work,” emphasises Baudson.

A contributing factor is how much each young star is disrupting what we perceive as the traditional life trajectory. “We tend to think of the life course and careers in stages, each with their own set of norms and milestones,” explains Hannah Swift, senior lecturer in social and organisational psychology at the University of Kent, who has researched ageism, equality and workplaces. “When one such milestone is met before these norms dictate, it can seem extraordinary.”

Chess prodigy Magnus Carlsen became a grandmaster at the age of 13, fascinating the world (Credit: Alamy)

That’s particularly true if achievements come early in certain fields. “We’re somewhat conditioned to seeing youthful poets and mathematicians, [whereas] novelists, philosophers and scientists [tend to be older],” says Jonathan Plucker, professor of educational psychology and talent development at Johns Hopkins University and president of the US National Association for Gifted Children. “Athletics offer similar examples, in that certain sports have superstars emerge in their teens, yet for other sports that is a rare exception.”

In today’s society, a young mega-achiever reaching new heights tends to be a newsworthy event. “Because media platforms are youth-oriented, achievements of younger people can be propelled and celebrated,” says Swift. “This perpetuates a cycle that under-represents [the success of] older people.”

Yet this cycle is a relatively new one. “Most historical societies took youthful contributions and labour for granted,” says Mary Jo Maynes, professor of history at the University of Minnesota. “Children and youth – in farming and working-class communities, at least – were expected to take on a huge realm of activities that we now regard as adult. These young people, as valued as they were, were not singled out for doing what was expected of them.”

With the evolution of Western society, however, ideas of what children should focus on pivoted away from work and responsibility toward school and play. “Modern Western understandings of childhood and development infantilise young people to an extent that produces low expectations,” says Maynes. “We are pleasantly surprised by young people’s accomplishments perhaps because we have relatively low expectations for the young.”

We love to laud people for amazing achievement – but only a little more than we like to take them down – Jonathan Plucker

And in a world with no shortage of negative headlines, sometimes a gifted young person doing something brave, beautiful or incredible is just the feel-good news we need. According to a 2016 study, positive news stories – including those about people overcoming adversity to find success – made readers feel happier than negative stories. “It’s human nature to be surprised by very early – or very late – examples of extraordinary achievement in life,” says Plucker. “We love the unexpected.”

The dark side of young success

As much as young go-getters’ triumphs can provide a vicarious thrill, however, they can also invite scrutiny and criticism. “I think most people have a love-hate relationship with precocity,” says Plucker. “In many Western societies, we love to laud people for amazing achievement – but only a little more than we like to take them down.”

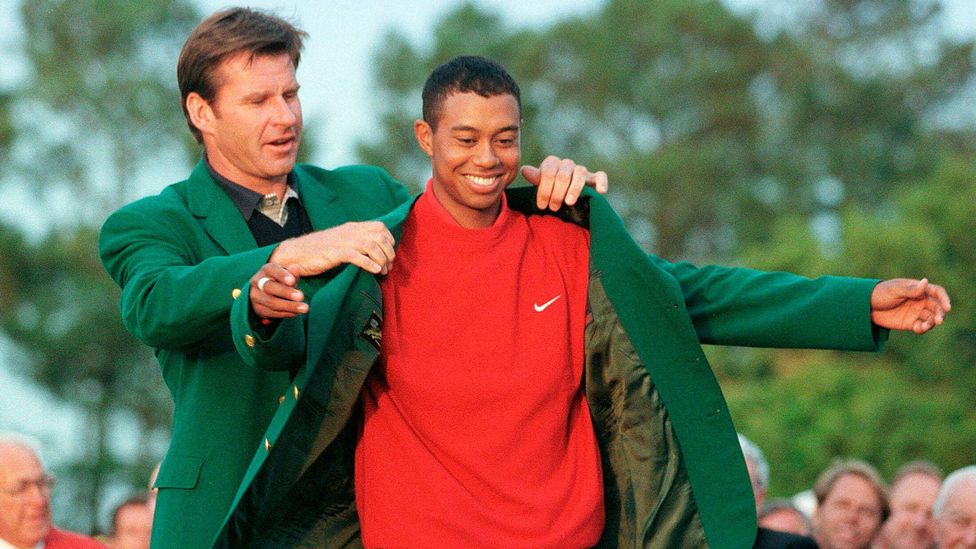

When 21-year-old Tiger Woods won the US Masters Tournament in 1997, he skyrocketed to fame for being the youngest person and first African American to win the prestigious golf championship. Yet when news broke in 2009 of the then-33-year-old’s reported marital infidelities, the headlines veered ruthlessly from his success to his poor personal choices.

Tiger Woods won the Masters at 21, but our attention ultimately turned to the negative headlines surrounding him (Credit: Alamy)

It’s not just salacious scandals that cause young achievers to disappoint. At age 14, US tennis player Jennifer Capriati was the youngest woman ever to win a match at Wimbledon, going on to win an Olympic gold medal at 16. But in the ensuing decade she struggled. Despite winning Grand Slam tournaments and hitting the top spot in the rankings toward the end of her career, much of the media narrative around her centres on the idea that she didn’t live up to her young promise.

Watching young prodigies fall from grace can trigger a feeling of schadenfreude among onlookers. “We love to see talented young people achieve impressive things, but there is also a sense of envy always lurking in the background,” says Plucker. Beyond jealousy, he says, negative emotions toward young achievers could be due to feeling that your own accomplishments are underappreciated by comparison.

Taking satisfaction in seeing gifted youth fail also goes hand-in-hand with the misconception that they haven’t worked as hard as others to succeed, says Baudson. By that logic, their downfall “restores the balance and belief in a just, meritocratic world, where people get what they deserve for hard work”.

But success is not a zero-sum game, and there are a litany of factors that contribute to success beyond natural ability and hard work, including personality, environment and support system. Just like the challenges that come with every age, life stage and skill level, the success that accompanies each will always be unique to each person.

“We should not make our own definition of success contingent on others’ success,” says Baudson. “We do not become better when others fail, and we do not become worse when others succeed. Bench-marking yourself against prodigies is unhelpful. “It makes more sense to apply a clear-cut criterion of what you want to achieve and focus on your personal progress.”

In the meantime, when young talents like poet Gorman rise to the fore, we can recognise them as the rare gifts they are, instead of holding them to impossible standards or judging ourselves for being less exceptional. Just like the feel-good headlines they spark, young stars can inspire and brighten our world for as long as they shine.

link: bbc.com

0 Comments